Up until 1956, the only way to reach Squamish was either by Ferry from Vancouver or by train from Whistler and, more likely, points north.

Then in 1959, a road link to the Lower Mainland was finally established and Squamish residents have complained about it ever since.

Now with the new highway and more people commuting to Vancouver and Whistler than ever before, the irony is, Squamish may need a train or ferry or both to help alleviate the pressure.

“It is an interesting conundrum,” said Squamish Mayor, Patricia Heinztman. “Commuters fill the highway now. We do want jobs in Squamish, but we’re always going to have commuters. There are just many more employment opportunities in Metro Vancouver.”

Of course, it is not just commuters. Squamish has grown as a tourist destination, which further adds to transportation woes on the highway.

“The tourist congestion issue is that it comes at high influx times and diminishes the visitors’ experience. As well, it diminishes locals’ ability to move around. Last Easter it took me two and half hours to get to Horseshoe Bay,” said Heinztman.

Eric Andersen, a Squamish Chamber of Commerce director and chair of regional transport, says the chamber has been looking at a number of presentations for various transportation solutions. Not to mention, the rest of the corridor’s chambers have been looking at alternative transportation solutions for years, if not longer.

“[Squamish] Chamber has been involved in planning regional transport solutions for decades. We’re asked by our members to be an advocacy group to local governments up and down the corridor,” said Andersen.

“The most important thing right now is to identify priorities for all modes, and to preserve infrastructure for bus, ferry or trains.” Looking at possible transportation systems that have been studied by the chamber, he ticks off some of the pros and cons.

“Bus — that’s the simplest solution, but as it is we have no coherent park-and-ride plan, it remains ad hoc. Ferry — we don’t have a marine strategy that identifies ports and investment needs. Train — the first question that has to be asked is, ‘Does the North Shore terminal have adequate infrastructure for a regular commuter/passenger train service?’ Then what about spur lines? What we’ve been doing in the entire corridor for years is tearing up spur lines. In particular, we removed track in Pemberton and Squamish. So again, we need to preserve options and make preserving infrastructure our first priority.”

Heintzman says a lot of study on alternative transportation solutions was done before the 2010 Olympics but hasn’t been addressed in a multi-faceted way since then.

“For the Olympics, it was decided just to put a ton of money into the highway.”

She notes more communication between local governments, and stakeholder groups is needed. “I think the biggest thing right now, is to stop doing isolated analysis. There are too many small plans in isolation. “

Almost to underscore that, the mayor was surprised to learn of a 2016 study by West Vancouver done in conjunction with UBC’s geography department. It was mainly an academic exercise, however, it did involve West Vancouver planning and transportation as well consultation from TransLink.

It proposed a rail link from North Vancouver, linking Lonsdale Quay, Park Royal, Dundarave, Squamish (possibly two stops), Whistler and Pemberton. It even went so far as to estimate ticket prices — $16 one way and $30 return (based on an undetermined government subsidy), without any subsidy the study estimated a ticket price of $25 one way.

“Well, when you factor in gas and parking for the day in Vancouver, a $30 return is about where it would have to be for it to make sense to commuters,” Heintzman said.

She added that commuter rail was discussed in some detail between the concerned governments at September’s UBCM (Union of BC Municipalities) in Vancouver.

“That was about a lesser train investment, not a high-speed rail idea. So we’re talking a North Van to Lillooet line. I talked with all concerned mayors about a via rail type of system, and we would be looking at about a $500 million investment for that.

“My understanding though is the existing (BC Rail) bud cars are not the most efficient. They need the ability to get up to 70 km. Now, I think, the most passenger cars can do is 50 km.”

Andersen is more unequivocal about the potential for rail, of any design, for the corridor.

“It won’t be high speed, it’s not physically possible, or it is, but the cost is enormous. That’s something you build through the Alps to connect countries. What are the transportation priorities of the province? We’re talking billions for a few tens of thousands of people.”

Andersen says that according to the West Coast Railway Association, 40 km/hour is the standard for rail travel in the corridor.

“Even with new technologies, to get trains going faster, it’s still, I think, cost prohibitive.

Heintzman concedes any hi-speed train option is a multi-billion dollar project, but not outside the realm of possibility, and notes that former premier Christy Clark included the idea of a hi-speed rail connection from Vancouver to Squamish in a pre-election speech last May. Furthermore, it has been an option considered by TransLink.

“Yes, the question is, how to pay for it, which probably means a huge expansion of real estate development through the entire corridor. Environmental groups want a high-speed train, but the catch-22 is with that, you get much more real estate. Anyone proposing that option has to understand that high-speed rail, even when paid by government, still means massive real estate investment.”

Of course, the easiest solution for commuter travel is to make use of the massive infrastructure already in place, the highway.

“We did a study a few years ago about buses. But one bus takes at most 44 cars off the road. You need a lot of buses to reduce traffic. Even if you put 10 buses on at peak time for Whistler, that takes at most 440 cars off the road. So we need to look at the whole gamut of transportation options to be considered,” said Heintzman.

She said a high occupancy vehicle lane might be a possibility.

“BC Transit has looked at it, but I don’t think they considered holiday/weekend traffic, and they didn’t consider Lions Bay, and how to dovetail with TransLink - their mandate does cover up to Pemberton. But you also don’t want to compromise our internal systems.”

However, as stated above, the problems of moving people through the corridor are about more than just meeting the needs of commuters.

“We need to meet the needs of tourists and commuters. Whistler’s tourist growth has been huge, Squamish is now attracting more tourists, and the Highway at peak times is nearing its threshold.”

Should Squamish make a deal with Translink on commuter buses?

“Personally, I think that’s the way to go,” says Andersen. “The gas tax is something we should look at. We’re not benefiting from that program, but in the end, we’re still paying higher gas prices.”

Then there is the link that originally tied Squamish to Vancouver. “A ferry has the advantage of being point to point. A rail link would just go to North Van. Also I think a ferry has the advantage of attracting tourists,” said Andersen.

The infrastructure for a ferry does exist, and the Darrell Bay ferry terminal is, to put it mildly, under-utilized, including its parking lot, which is not being used or commercialized in any way.

“When Darrell Bay was built (to ferry workers to Woodfibre across Howe Sound) there was no coordination with Squamish, the province just went ahead and did it,” says Andersen.

“Back in 2001 a business case was done for a potential ferry,” said Heinztman. “This was part of the transportation scenario for 2010. The business case then, was that it was workable for Darrell Bay... The idea was considered very viable, just for passengers, and it would be a Vancouver to Squamish shot only, so that has its limitations as well.”

She said there is no plan for a ferry terminal on the oceanfront lands, although there is a mini-cruise ship terminal, which could, in all likelihood be adapted for commuter ferries.

Bill Cocksbridge of Slipstream Vessels says he was approached by investors about using one of his vessels on a Squamish to Vancouver ferry route. His company is developing a high-speed air cushion vessel that could travel speeds of up to 120 km per hour.

“I spoke to council there a couple of years ago, and there was certainly interest in getting a commuter ferry operating. But I’m not in the ferry operating business, I’m in the shipbuilding business,” said Cocksbridge.

Although he adds, the 200-passenger craft he envisions running the Squamish to Vancouver route would be fast enough and have a shallow enough draught to include other stops on the way.

“I do think the marine interface Squamish had needs to be recovered. We’ve been too preoccupied with housing and parks.”

Heintzman says going forward all transportation options have to be considered.

“But we have to address those options more comprehensively. Although I am optimistic that there will be a near-term solution for the corridor,” said the mayor.

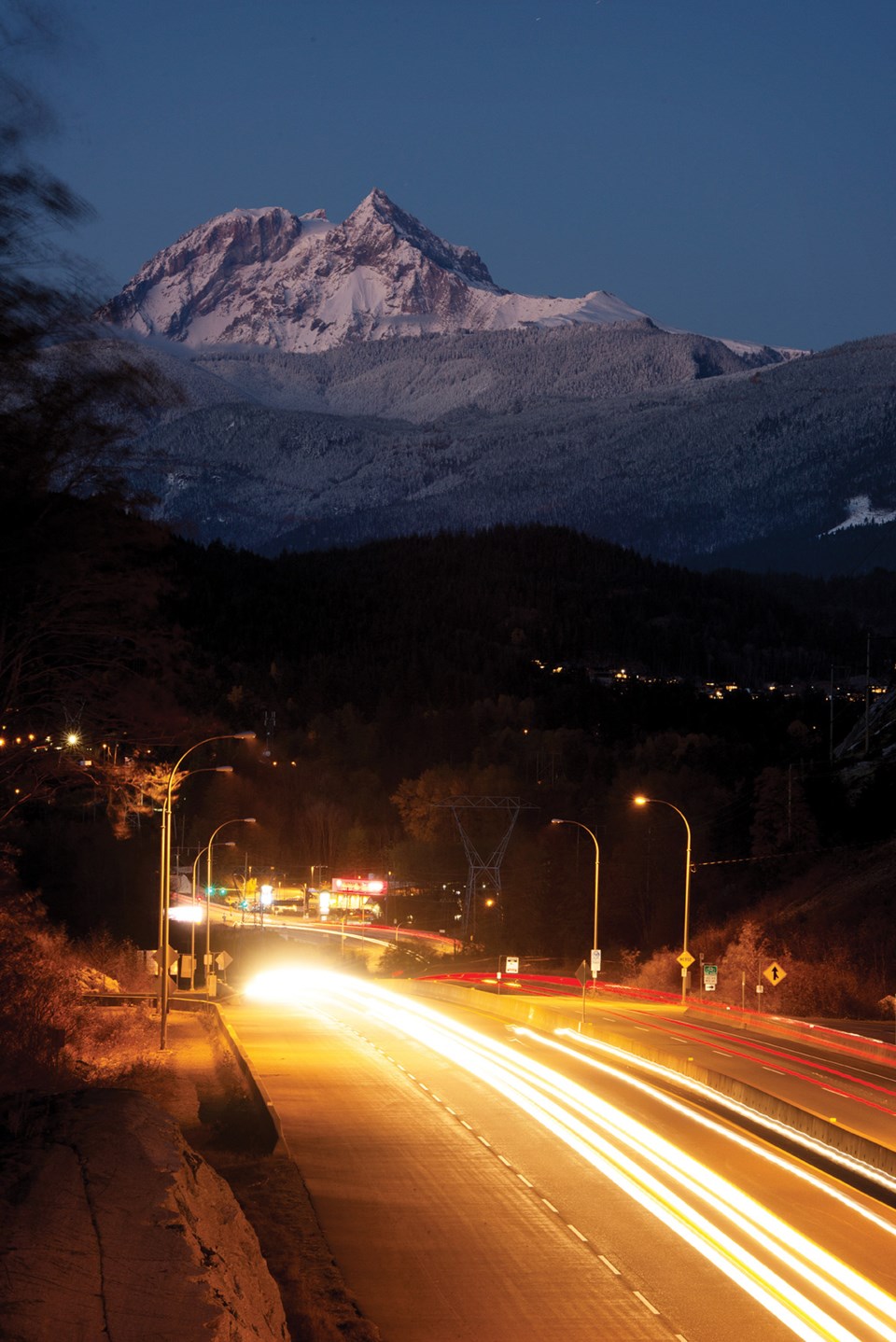

Photo by David Buzzard/For The Squamish Chief.