So NASA says it’s going back to the moon by 2024. What a colossal waste of money.

Since 1958, there have been 140 lunar missions, some intended to encircle the moon, others to land on it. Roughly half failed on lift-off or in flight, and nearly all of the remainder were, for the most part, trial runs aimed at developing more reliable technologies.

The issue revolves around diminishing marginal returns, the idea being that the more often you attempt a venture, relatively speaking the less you stand to gain.

That wouldn’t be true if all of the moon-shots so far had failed. In that case, it would still be worth another try.

But six manned missions (all American) have landed on the surface and returned safely. What is to be gained by a seventh, considering the miserable failure rates to date?

It’s been suggested that the moon could be mined for minerals that might in turn be processed on site as fuel for missions further afield.

No doubt one day this might be practical. But by 2024? Not a chance.

This is merely another placeholder in case Congress shuts down the space program completely.

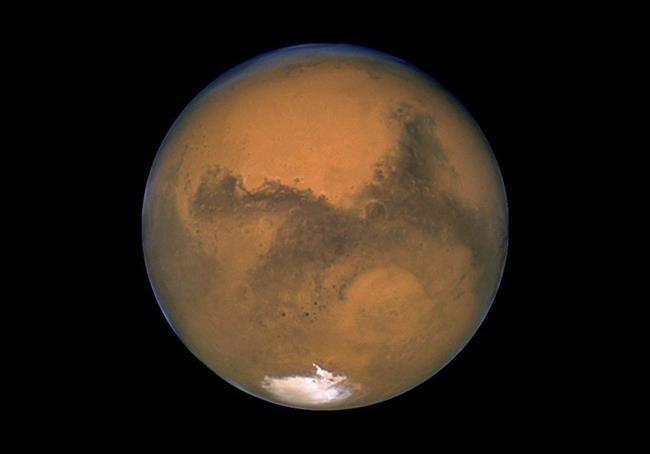

The more obvious target is Mars. A recent stream of data from orbiters and landers, as well as Earth-based telescopes, has shown that without question water remains on that planet. Most of it will be underground — the atmosphere has burned off to such a degree that liquids don’t survive long on the surface.

Even so, there are photographs of water trickling down the sides of craters in the polar region.

To date, the robot landers sent to Mars have been miserably limited in nature. Their ability to search beneath the surface extends to only a few centimetres.

Clearly, that won’t do. If there is life on the red planet — the main reason for going there — it is likely to be far underground, possibly in subterranean caverns.

But the rovers sent to Mars have no chance of reaching these. At best they can test for atmospheric gases that might, conceivably, suggest the presence of living organisms.

And the emphasis here is on “conceivably.” There are numerous alternate explanations that skeptics will point to.

We’ve been conducting radio searches across various sectors of the galaxy since the late 1950s, looking for signs that someone is out there. So far, we’ve found nothing. Not that this has disheartened SETI researchers, who like NASA, need an excuse to stay in business.

The only realistic means of proving we are not alone in the universe is to visit the one planet in the solar system that has both a history of life-sustaining conditions, and which is within the reach of a manned expedition (if only just).

There is no question about the difficulties or risks involved. Given current rates of acceleration, it will take a ship about seven months to reach Mars, and the same to get back.

That’s a long time in a gravity-less environment. You could perhaps spin the ship to create the equivalent of gravity, as was done with the fictional Soviet spacecraft Leonov in the movie 2010.

But no-one knows the effect this would have on the human body over an extended period.

Then there is an unavoidable wait of 18 months on the planet’s surface until the Earth orbits back into the proper position. But the average temperature is -63 C, and radiation levels (again due to the thin atmosphere) are far above the lethal level. We’re talking mammoth hazmat suits.

Nevertheless, if we’re going to face the risks that manned space travel involves, we might as well do so for a purpose worth pursuing. Proof that we are not alone (and I’m betting that’s what such a mission would show), is the only purpose that meets this test.