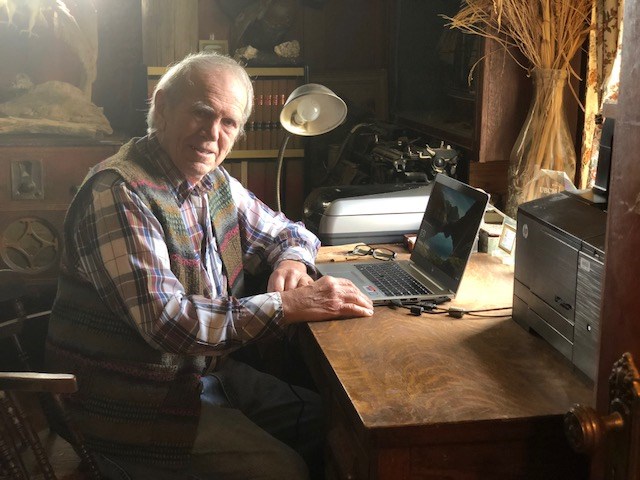

Richmond Coun. Harold Steves is sounding the alarm around food insecurity and the coronavirus (COVID-19) outbreak.

He is personally seeing demand for seeds that he sells at his farmgate increase dramatically, and he thinks that’s a result of people worried about finding fresh produce if this pandemic continues long-term.

Steves, who is well-known regionally as an advocate for local food security, is not sure what will happen if this crisis continues for two to three months given that B.C. is largely dependent on its fresh produce coming from California where they’re not just dealing with COVID-19.

“California is hit with two things now – they’re hit with major drought because of climate change and then the coronavirus,” Steves said. “We have no idea how it’s going to affect the food supply (in B.C.).”

Not only are his seeds flying off the proverbial shelf, Steves’ son, who grows organic beef in the Interior, has already pre-orders for all the beef he was going to butcher in May.

“Those that are producing locally are overwhelmed,” Steves said.

The panic around food can be seen in grocery stores as shelves are emptied almost daily of basic necessities – eggs, milk, butter and, of course, toilet paper.

Grocery stores have been quick to say there is plenty of supply, but they just can’t get it on the shelves as people resort to hoarding.

Like B.C. and much of North America, California is under a state of emergency because of the COVID-19 outbreak, and they currently have about 10,000 cases.

Kent Mullinix, director of Sustainable Agriculture and Food Security at KPU, echoed Steves’ concerns about the coronavirus adding to the stressors of California’s food production system.

“California as a supplier of fresh fruits and vegetables to Canada or any place else cannot be relied on going forward – in the face of climate change and other challenges like this pandemic,” Mullinix said.

Those regions like B.C. that are dependent on the global food system created to supply daily necessities will be in “significant jeopardy” with dire consequences if the system breaks under a catastrophe, Mullinix said.

While B.C. farms use the labour of about 10,000 migrant workers, much of it from Mexico, California is “entirely dependent” on this transient labour. Given restrictions on travel during the pandemic, some are wondering whether the workers will arrive on the farms.

Mullinix said it’s hard to speculate accurately or without seeming alarmist on how COVID-19 will affect the food supply chain.

“But this absolutely illustrates the house of cards our food system – and our economy – is, unequivocally,” he said.

This is why it’s imperative B.C. start diversifying its food supply, he added, to lower the risk in the event of a catastrophe.

Climate change and other indicators are signalling that B.C. needs to “get all our eggs out of a single basket and build strong, robust, local regional food systems,” Mullinix said.

“When we do this, the economic rewards will come to our communities,” he added.

Mullinix points out there is a parallel between the U.S. government's lack of response to climate change and its lack of preparedness for a pandemic, not heeding scientists who were warning them to prepare.

“They failed to listen, now they’re a mess,” Mullinix said. “The same thing is true with global supply chain, this global food system.”

Meanwhile, Steves is encouraging Richmond residents, and others, to plant what was called a “victory garden” during the Second World War - even if it’s just in pots on a porch.

During the Second World War, when food was rationed and much was sent overseas to support the military, Canadians and Americans grew 42 per cent of their own produce in their own gardens, Steves explained.

But since then, very few people grow their own food, and there is no plan for local food security, Steves said.

"It’s finally coming to a head that we have to deal with food security and the public are demanding it,” he said.

For more COVID-19 coverage, go here.