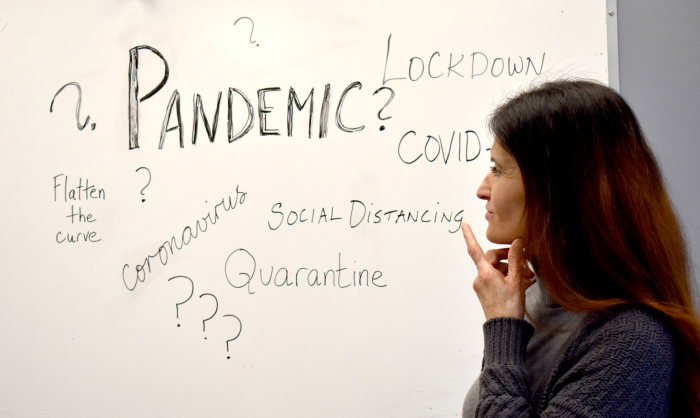

The COVID-19 pandemic – which, as of the time of publishing, has infected over 400,000 people across 196 countries and territories since it originated in central China in late 2019 – has introduced a number of new words into our collective vocabulary.

Here’s what they mean:

Coronavirus

Coronaviruses, which can affect both humans and animals, are a large family of viruses that can cause a range of illnesses, from the common cold to more severe diseases like SARS and MERS.

The current virus spreading around the world is a new coronavirus, which is why it’s also referred to as the novel coronavirus.

COVID-19

The novel coronavirus causes COVID-19, which stands for “coronavirus disease 2019.” The disease was named by the World Health Organization Feb. 11.

Symptoms include a high fever, coughing and shortness of breath.

COVID-19 is believed to have originated in bats, and likely passed to humans via an intermediary animal.

SARS-Cov-2

There is also a name for the novel coronavirus, SARS-CoV-2, to reflect its similarities to SARS.

This novel coronavirus or SARS-CoV-2 causes the coronavirus disease, COVID-19.

Zoonotic disease

A zoonotic disease is one that passes from animals and humans, for example, rabies, SARS and ebola.

COVID-19 is believed to have originated in bats, and likely passed to humans through an intermediary animal.

Asymptomatic

A person is asymptomatic when they don’t show any symptoms of COVID-19 (or another illness).

Incubation period

An incubation period is the amount of time it takes for an infection or disease, such as COVID-19, to develop and for people to have symptoms, after being exposed to the virus.

The incubation period of COVID-19 is about 14 days, which is why health officials recommend self-isolation for two weeks if you’ve been travelling abroad or have had contact with someone with the coronavirus.

Mitigation

Canada’s public health agency has developed guidelines for community-based mitigation measures – measures used to “reduce and delay the spread of COVID-19 in the community.”

Mitigation measures include, among others, practices like social distancing, washing your hands, cleaning frequently-used objects and surfaces and limiting crowd sizes.

Social Distancing

Social, or physical, distancing means you are taking steps to limit the number of people you come into close contact with, and limiting contact with people at a higher risk of contracting COVID-19, so you don’t pass along the virus.

This is one of the ways people can help flatten the curve of COVID-19.

Social distancing measures include keeping a distance of two metres away from others, avoiding crowded public places or public transit, and staying home as much as possible.

Self-isolation vs. Quarantine

Self-isolation is a voluntary quarantine, meaning you are ideally not leaving your home, even for groceries, and you aren’t visiting friends, family outside your household or neighbours. People who are self-isolating need to stay home for 14 days, in case they develop symptoms of the coronavirus.

It’s recommended for an asymptomatic person when they have a high risk of exposure to COVID-19, such as people returning from travel abroad.

A “quarantine,” on the other hand, is imposed by health or government officials for a specific length of time, and can be applied to individuals or to groups. For example, Canadians who were repatriated from Wuhan or the Diamond Princess were placed in a mandatory 14-day quarantine at CFB Trenton.

Flattening the Curve

When health officials and researchers talk about a curve, they are referring to the number of people who are projected to contract COVID-19 over time, as a way to model the spread of the virus.

Depending on the rate of infection and community mitigation measures, the curve can take on different shapes.

A steep curve shows a pandemic with no intervention, and a high number of cases reported at one time. In this scenario, the healthcare system can quickly get overloaded – which is the case in Italy, where an increasing number of patients don’t have access to ICU beds and hospitals may run out of supplies or equipment.

By flattening the curve through mitigation measures, the health care system is less stressed and not overburdened at any one time, and the number of cases reported at the same time is diminished.

Contact tracing

Once someone has tested positive for COVID-19, health officials begin contact tracing, meaning they work to identify who that person was in contact with, as those people may also become sick.

Pandemic vs. epidemic

The World Health Organization declared COVID-19 a pandemic March 11.

While there is no clearly-defined threshold for a pandemic, it’s declared once simultaneous outbreaks of a new disease, regardless of severity, have appeared worldwide.

An epidemic means there is a rapid spread of a disease within a specific community or region.

Public health emergency

A public health emergency is declared by the provincial health officer. Currently, B.C. is in the midst of two public health emergencies: one declared in 2016 in response to the opioid crisis, and one declared last week for COVID-19.

Under a public health emergency, which is declared under the Public Health Act, the provincial health officer has the power to verbally issue orders that are immediately enforceable – such as the order from Bonnie Henry, B.C.’s provincial health officer last week for all bars and restaurants across the province to halt dine-in services.

Henry can also call on peace officers to enforce her orders.

In addition, Henry can authorize health-care workers to do their work anywhere in B.C., rather than just in the health authority region where they were hired.

The B.C. Minister of Health, Adrian Dix, has the power to amend regulations without the consent of cabinet. He can also make changes to the Public Health Act without the consent of the legislature.

Lockdown

Lockdowns have been imposed by various governments around the world to try to slow the spread of COVID-19.

For example, Italy, the UK, China’s Hubei province, and Peru are all under mandatory, government-regulated lockdowns, as are California and the state of New York.

In most cases, this means people cannot leave their homes except to buy groceries, solitary exercise like a walk or a run, or go to work if they have to. All non-essential businesses are shut down, but transit and roads are not affected.

However, in Hubei province, China, people were effectively banned from leaving their homes, and bus and rail service was suspended. India has now banned people from leaving their homes for 21 days, while domestic flights have been grounded, international flights banned and rail service suspended.

Governments can impose fines if the rules aren’t followed, and police can enforce those rules.

Essential services

How provinces define essential services can vary, but the federal government defines them as services that are “critical to preserving life, health and basic societal functioning.”

This can include, but isn’t limited to, health care workers and first responders, critical infrastructure workers and hydro/natural gas workers, and grocery, pharmacy or supply chain workers.

Ontario, for example, has deemed gas stations, restaurants with takeout or delivery services and beer, wine and liquor stores essential. In addition to pharmacies, grocery and convenience stores, pet food stores are also essential.

For all the latest news on COVID-19, click here.