The cities of ancient Mesopotamia were oases for travelers trying to escape the sun’s heat.

Urban shade was created by the buildings themselves with homes constructed close together and next to alleyways less than 5 feet wide. Communities were built on diagonal grids offering equal amounts of sun and shade throughout the day for both buildings and street surfaces. Buildings were taller than the streets were wide, allowing surfaces to rest longer in the shade.

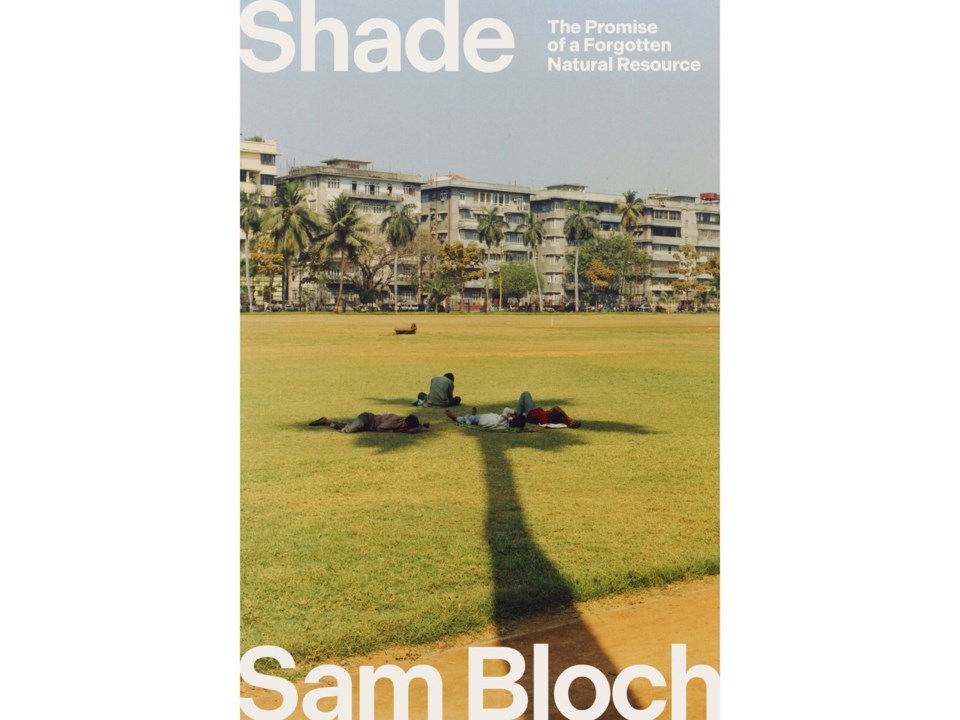

In his new book, “Shade: The Promise of a Forgotten Natural Resource,” environmental journalist Sam Bloch encourages us to look to the past for solutions to our ever-warming urban areas as climate change creates heat waves that are more frequent, hotter and longer lasting.

Bloch’s call for more shade in urban areas, with more trees in parks and residential areas and new ways to design public areas and buildings, comes as policy makers grapple with a growing crisis in heat-related illness and death.

He notes that better shade and access to water is critical for people working outside, such as California farmworkers and the laborers who died by the thousands in the hot, arid country of Qatar while building facilities for the 2022 World Cup.

Bloch says people in ancient times understood this far better than we do. Shade was once considered an important resource in cities where people went about their daily business outside in the summer heat. In the medina of Fez, Morocco, some buildings are 10 times taller than streets are wide, allowing the bottoms of the street canyons to remain shaded all day. Bologna, Italy, enjoys 38 miles of covered sidewalks with covered porticoes that have shielded pedestrians for 1,000 years.

Even in modern times, some Spanish cities have used huge curtains called “toldos” to hang over streets to protect pedestrians from the fierce summer rays.

In the United States, awnings were once popular in some cities, but urban planners moved away from shade because of widespread beliefs that dark spaces could be unhealthy and spread disease. Streets were made wider, then wider still to accommodate automobiles. Zoning laws required buildings to be more open to sunshine.

Without significant shade elements, new buildings depended more on central air conditioning, which releases hot air that adds to the urban heat island effect in many larger cities.

Bloch’s book has good ideas that architects and policy leaders can embrace to better use shade to protect people from the world’s increasingly hot weather. For instance, he describes passive homes that are designed to stay cool without the use of energy. He points to heat-conscious countries like Singapore, where trees are contemplated in overall designs before construction projects begin.

Bloch wants everyone to pitch in to combat global warming, but says collective planning, management and action is needed to get results. Simple, low-tech solutions like improved building designs and increasing the number of trees planted in our communities can make a difference, he insists.

He notes that lizards, insects and fish all instinctively seek shade. Creating more and better shade for human beings, he says, could be among our most powerful defenses against rising heat.

___

AP book reviews: https://apnews.com/hub/book-reviews

Anita Snow, The Associated Press