What you need to know:

- A BC Coroners Service report finds 619 people are now thought to have died during the 2021 heat wave in B.C.

- The B.C. government has taken first steps to close a gap in emergency warning and response.

- The report sets a number of goals, from an investigation into providing cooling devices as medical equipment to changing building codes to ensure retrofits and new builds are designed with extreme heat in mind.

- As tree canopies decline and more people live alone in B.C.’s cities, experts warn a lesser heat wave could be even deadlier.

- Solutions include densifying and greening neighbourhoods at the same time, something experts say needs to be backed by an amended Local Government Act.

A long-awaited investigation into deaths during Canada's deadliest heat wave has upped the human toll while laying the groundwork for authorities to protect British Columbians from the next round of deadly heat.

On Tuesday, the BC Coroners Service adjusted the number of deaths attributed to the June 2021 heat wave to 619, up from 595 previously reported.

The review into human mortality during last summer's extreme heat also placed partial blame on government agencies that failed to respond properly, stating there was a lag between the heat alerts issued by Environment and Climate Change Canada and public agencies and the public response.

"We're talking about any sort of agency that had anything to do with the response," said BC Coroners Service chief medical officer Dr. Jatinder Baidwan, pointing to everything from local and provincial governments to the province's ambulance service.

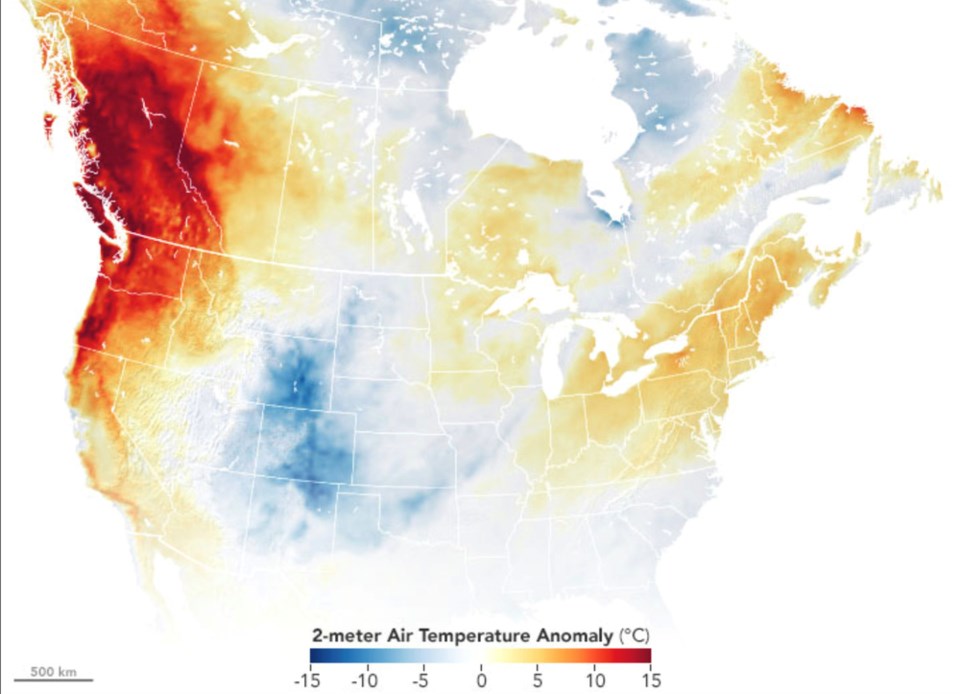

Now known as the 2021 North American heat dome, temperatures began to rise on June 24, later peaking on June 28 and 29. As records fell across Oregon and Washington state, temperatures climbed to over 40 C in many parts of B.C. The town of Lytton reached just shy of 50 C, only to burn in a wildfire the next day.

And in a deadly turn, overnight temperatures remained elevated, preventing many people from getting respite from scorching daily temperatures.

Nearly a year later, the BC Coroners Service has found some clear patterns in how people died: 98 per cent of deaths occurred indoors, and deaths were higher among those with chronic diseases like schizophrenia, substance-use disorder, epilepsy, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, depression, asthma, mood and anxiety disorders, and diabetes.

Roughly a third of the victims of heat were 70 or older, and 56 per cent lived alone. Most deaths occurred in homes without fans or air conditioning.

And in line with a Glacier Media report looking into how and where people died in the City of Vancouver, where most deaths occurred, more people lost their lives in "socially or materially deprived neighbourhoods." That includes poorer households with less access to green space, recreation and education, as well as those who live alone, as a single parent or are separated, divorced or widowed.

The fallout is only expected to get worse. In the weeks following the heat dome, climate scientists found the heat wave was made 150 times more likely due to human-caused climate change. By the 2040s, such events could occur every five to 10 years.

Modelling released earlier this year concluded several cities in British Columbia are likely to face some of the most extreme heat in the coming years, with Kelowna projected to face the longest-lasting heat waves and the hottest maximum temperatures of any major Canadian city.

But it's not just the hottest cities that are expected to get hit hard — in urban areas where a "heat island" effect elevates temperatures and many residents are not used to extreme heat, deaths can soar.

On a regional scale, the latest coroner's report found three-quarters of the deaths from last year's heat dome occurred in the Fraser and Vancouver Health authorities, with Fraser North (Burnaby, New Westminster, the Tri-Cities and Maple Ridge-Pitt Meadows), Fraser East (Hope, Chilliwack, Abbotsford, Mission and the Agassiz-Harrison area) and Vancouver recording the highest death rates.

The report found that at the peak of the heat dome, 911 calls doubled, reflecting a near collapse of emergency ambulance services, with some firefighting crews reporting up to 11-hour wait times for a hospital transfer and others calling taxis in desperation.

In the end, paramedics attended 54 per cent of the deaths due to extreme heat. And while the median wait time was roughly 10 and a half minutes, in 50 cases, ambulance crews took over half an hour to arrive. The report also said that in 17 cases, patients were put on hold for extended periods, and in six cases, callers were told no ambulance was available.

The BC Coroners Service recommends government roll out a provincial heat alert and response system — something the B.C. government announced a day before the BC Coroners Service report was released.

The report also called on governments to find and support people most at risk of dying during an extreme heat emergency and to roll out a number of short- and long-term measures to protect them.

Citing national extreme heat guidance published earlier this year, the report points to a number of building retrofits that would shade and cool vulnerable people in poorly ventilated units.

But in some cases, an emergency response may require drastic measures. By Dec. 1, 2022, the report says the Ministry of Health and the Ministry of Social Development and Poverty Reduction should carry out and release a review looking into whether cooling devices should be treated as medical equipment and be made available to vulnerable people most at risk of dying.

In a call with reporters Tuesday, Minister of Emergency Preparedness Mike Farnworth and Minister of Health Adrian Dix said the government was committed to carrying out the recommendation.

If not in their homes, Baidwan said the alternative would be to transport them to a cooling centre where they won't be at such a high risk.

"There'll be some loss of personal autonomy that happens obviously, but on bet on a balance of risks, that's probably the right thing to do," said Baidwan.

B.C. government bolsters emergency response

In a nod to the human tragedy that unfolded under scorching conditions, both the report and Baidwan paid tribute to the families, friends and communities of those who died.

"May their memories endure in our actions to prevent similar deaths in the future," reads the report's dedication.

The report — conducted by a number of high profile experts in public and First Nations health, emergency services, as well as public housing, poverty reduction and city planning — called on the B.C. Ministry of Health, provincial health authorities and Emergency Management BC to adopt and institutionalize the BC Health Effects of Anomalous Temperatures (BC HEAT) Committee to oversee province-wide emergency responses.

That plan — the Heat Alert and Response System (HARS) — was announced to the public June 6 in what appears to be a coordinated release with the BC Coroners Service report. It includes plans to bolster the staffing of ambulance crews and a new emergency notification system that beams out an intrusive broadcast over text, radio and TV when temperatures reach certain extreme thresholds.

According to the coroner's report, the HARS plan should be forwarded to local governments by June 30, so they can adopt its guidance, such as mapping out and checking in on vulnerable residents, creating mobile and fixed cooling centres, distributing water, and ensuring there are "greening areas and cooling parks."

Governments, says the report, should recognize extreme heat as a "natural disaster" on par with flooding and wildfires.

Baidwan said authorities have made significant process in planning for the next heat wave but warned much more needs to be done.

"You are never going to live in a society where you eliminate all risk, but we have to do our utmost to ensure that we absolutely actively eliminate as much risk as we can understand," he said.

The emergency response measures are just the first step in closing the gap extreme heat poses to public health. Some experts worry some of the biggest factors that make extreme heat risky are going unaddressed by the provincial government.

Balancing development with trees

Long-term, the coroner's report highlights poor city design as a leading contributor to rising temperatures. City centres, where concrete and glass dominate the landscape and trees are scarce, create ideal conditions for a growing "heat island" effect.

Last year, Glacier Media reported hospital emergency room visits tripled in some of Vancouver's most deprived and tree-starved neighbourhoods, where temperatures soared.

The coroner's report found roughly a third of those who died last summer in the heat wave lived in such neighbourhoods.

"A number of deaths occurred in neighbourhoods with large roads, large buildings, high density, and low greenness," states the report.

Green spaces can drop neighbourhood temperatures roughly 12 degrees celsius, and modelling in Vancouver has shown a pedestrian standing in the shade of a tree can experience temperature reductions of up to 17 C.

But in Metro Vancouver, where most of the deaths occurred, scores of municipalities face a steep decline in their tree canopy.

Artificial cooling also failed many people who needed it most.

The report found only seven per cent of those who died had air conditioning. It called on the Ministry of Environment and Climate change Strategy to ensure rebate programs for upgrading and cooling homes should be focused on census areas where poverty was most acute.

Focusing on single units in even the most deprived neighbourhoods can also obscure a wider systemic problem.

"We historically live in an area where we worry more about heat, and we worry about sort of keeping the heat inside the building. And now that's kind of biting us," said Baidwan.

"People dying from heat, it's a failure of the way that we live."

The report calls for the province and municipalities to revise building codes to reflect the latest climate science and the risk extreme heat poses to British Columbians. By the summer of 2024, the report calls on the Ministry of Attorney General and Responsible for Housing to ensure that a revised building code includes both passive and active cooling requirements in new housing construction and that retrofit codes do the same for renovations.

At the same time, more work needs to be done to reshape not just what B.C. builds but how communities let the forest and its shady benefits back into the city.

Michael Brauer, a professor at the University of British Columbia's School of Population and Public Health, said the coroner's report was impressively comprehensive.

"It pretty much covers all the bases," said the expert in extreme heat and air pollution.

But in practice, he said it's relatively easier to find and help vulnerable people in poorer neighbourhoods like Vancouver's Downtown Eastside, where people who need assistance are concentrated. In mixed residential neighbourhoods, many older people living alone with language barriers are harder to reach.

"I actually would have liked to see this implemented this summer," he said.

Brauer says he's concerned the province is focusing on emergency response without moving forward on addressing poor housing and city design — the root causes leading to the deadly effects of urban heat.

"You're up against developers and money," he said. "I don't think we want to see something where we're removing mature trees and putting in, you know, young trees that are going to take 15 to 20 years to provide any reasonable shading. That's really not the way to go."

With another million people expected to make Metro Vancouver their home by 2040, Brauer says a big question centres around what cities will do to ensure major development plans, in places like the City of Vancouver's Broadway corridor, are designed so people can survive extreme heat.

"All those buildings also are, in some ways, actually generating heat too," he said. "This may mean a call for more kind of low-rise, mid-rise and not high-rise type construction where you can preserve a lot of the tree canopy, where you can get the benefits of shading."

Alex Boston, executive director of Renewable Cities at Simon Fraser University and a member of the panel that produced the coroner's report, said that the province should be commended for moving forward on strengthening its emergency response to extreme heat.

But when it comes to long-term prevention, he says the province is failing.

Over the next 15 years, if B.C. were to have another heat wave even a shadow of the strength of the 2021 heat dome, Boston says the results could be even deadlier.

"The fundamental underlying trends that make us vulnerable are growing — and that is, number one, the rapid decline in urban tree canopy, but number two, the explosive growth in senior and one-person households."

He says the province has already acknowledged that guarding against climate change's effects requires rethinking regional growth strategies — the plans that decide how cities are developed.

Boston says it's time to update the Local Government Act to integrate policies that preserve tree canopies across B.C.'s urban areas. When asked how the B.C. government is planning to address declining urban tree canopies, Minister Farnworth deferred to municipalities without committing to any province-wide response.

Since the 1990s, Boston says protecting trees on new single-family lots has been increasingly more difficult than with multi-family developments.

But policies to grow green spaces while densifying housing has been shown to work in places like Singapore, said Boston.

"These things are not mutually exclusive," he said, pointing to the Broadway corridor project in Vancouver.

"The limitation in the Broadway plan is precisely this omission of robust consideration of green space [and] urban tree canopy — and that needs to be strengthened."

The plan to densify neighbourhoods dominated by single-family homes and house the next generation of Vancouverites offers a perfect chance to integrate a massive linear park adjacent to the SkyTrain, added Boston. In addition to lowering neighbourhood temperatures, it would provide residents with a long list of other benefits, including reducing the incidence of chronic disease and bringing people together to connect.

"The solutions are there, and it's stuff that isn't hugely cost-intensive," he said. "[It's] about taking advantage of public land and using it far more effectively."

"It's a win-win-win all around."

.jpg;w=120;h=80;mode=crop)