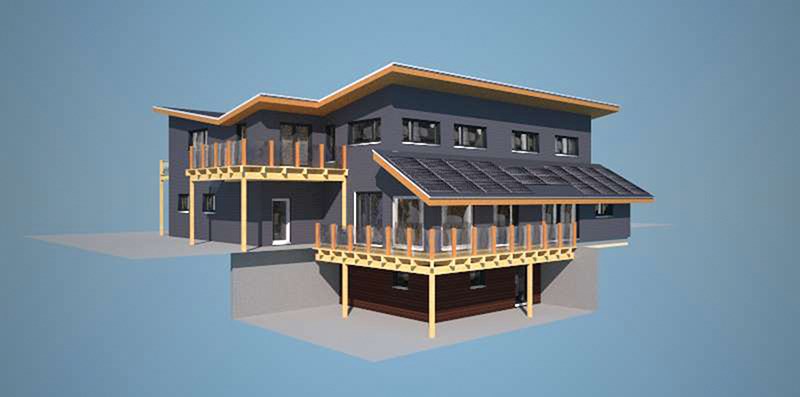

Homeowner Tom Grimmer surveys the construction workers assembling his unique home on a lot overlooking the Comox Glacier on Vancouver Island.

His four-bedroom, 2,600-square-foot passive house is Squamish-designed and constructed by sister companies Factor Building Panels and British Columbia Timberframe.

“You have a place that is designed in such a way you don’t need to add any energy to it,” Grimmer said. “It is an idea that has always been attractive to me… We need more positive innovation like this.”

A passive house is built differently to be highly energy efficient.

Through a more efficient building shape, solar exposure, super insulation, air tightness and ventilation with heat recovery, a passive home conserves 80 to 90 per cent of the energy used in conventional construction, according to the Canadian Passive House Institute.

Grimmer’s house is actually called a “passive house plus,” meaning it is more efficient and will also generate energy at certain times of the year that will be sold into the BC Hydro grid.

It is one of the first houses of its kind in B.C., according to Kelvin Mooney of BC Timberframe.

His house cost about 15 per cent more to construct than a regular house, according to Grimmer. Other industry experts estimate a passive house costs about 10 per cent more to construct that a house built to code.

Once the foundation is poured, it takes two weeks to complete.

“It just goes together like Lego,” he said.

Mooney said that eventually the building code will change and everyone will have to build passive houses.

He blames the weaker current building codes as the reason why more passive houses aren’t being built in the corridor.

There are close to 60,000 registered passive units worldwide, according to the International Passive House Association, and 22 in B.C. according to the Passive House Database.

Grimmer argues that energy has been too cheap in Canada for too long, creating a disincentive for conserving it.

“That is why we don’t have electric cars, that is why we don’t have [lots of] passive houses,” he said.

But the way we have traditionally constructed buildings hurts the environment, experts argue.

The energy sector – oil and gas industries – produces the largest amount of greenhouse gas emissions in B.C.; major sources for those emissions include transportation and “stationary combustion sources,” such as heating buildings, according to the provincial government.

The City of Vancouver has been campaigning for residents to build passive houses for years.

The push is part of its council’s goal of being completely dependent on renewable energy by 2050.

The aim is to eliminate greenhouse gas emissions from new buildings by 2030.

‘The way of the future’

The idea of a passive house is not new. The concept was first discussed in North America decades ago in reaction to the oil crisis in the early 1970s, according to the U.S. Passive House Institute.

Since then, the concept has been perfected.

Beyond its environmental and conservation benefits, living in a passive house just feels better, said Matheo Durfeld, CEO at BC Passive House, based in Pemberton.

Passive homes are prefabricated in the company’s 16,000-square-foot plant.

Durfeld’s company built Canada’s first residential passive home in Whistler and the plant is Canada’s first manufacturing plant of its kind that meets the international passive house standard.

“It is the most comfortable, healthiest thing to live in,” he said, simply.

Several studies have found that living in “greener” buildings helps increase productivity and reduces illness; one 2009 study found employees took five less sick days per year when they worked in a passive office.

The ventilation and health of a school building impacts a child’s ability to learn, a 2017 U.S. report, Schools for Health, states.

Passive homes don’t get the mould some typical builds attract and they have fresh air vented in regularly throughout the day.

Durfeld said the owner of one of the homes his company built told him that when the Sea to Sky Corridor was socked in with smoke earlier this summer, it didn’t come into her home.

There are no restrictions on building passive housing in the District of Squamish.

Council has directed staff to create incentives for designing and building beyond the requirements of the current BC Building Code through its Strategic Plan.

Future incentives will not be specific to passive design, but for specific components such as insulating to a higher value, according to District staff.

Coun. Susan Chapelle has built an energy-efficient home, though not an officially “passive” house.

A home builder can create an energy efficient home that is almost as good without the expense of being certified passive, she said. “You can build ‘passive’ where energy use is thought about and where choices can be made along the way. If a home is built with efficiencies, such as triple pane windows, hot water on demand or a solar water heater, it will have the exact same outcome as certified, meaning low-energy consumption,” she said.

Everyone seems to agree that more energy efficient homes are the way of the future.

Chapelle argues the planet depends on it.

“If we could build our living areas as higher density with better insulation, it could be the highest source of greenhouse gas reductions per person in B.C.”

Passive house standard

To meet the international passive house standard, a house must meet these criteria:

- Space heating demand: not to exceed 15kWh annually

- Space cooling demand: roughly matches the heat demand with an additional climate-dependent allowance for dehumidification

- Primary energy demand: not to exceed 120kWh annually for all domestic applications (heating, cooling, hot water and domestic electricity) per square metre of usable living space

- Air-tightness: maximum of 0.6 air changes per hour at 50 Pascals pressure

- Thermal comfort: thermal comfort must be met for all living areas year-round with not more than 10 per cent of the hours in any given year over 25 C*

~From the International Passive House Association