What was previously pioneering of the vertical realm has become something entirely different.

Today’s rock climbers are out for an adventure when embarking on a climb up the Stawamus Chief, but it’s a different game now – one in which there is specialized equipment and better knowledge of what lies ahead.

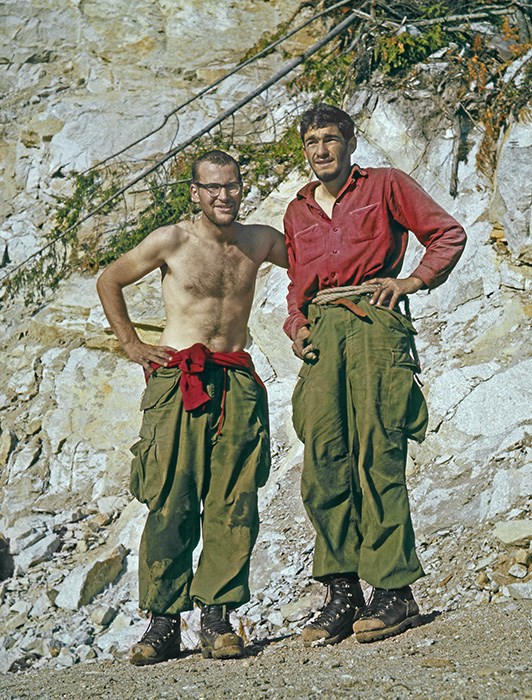

It was 55 years ago this past June that Ed Cooper and Jim Baldwin were the first to climb the Chief. Their literal ground-breaking ascent went directly up the Grand Wall, the prominent blank expanse below the First Peak.

Baldwin and Cooper persevered over four weeks, advancing their position up the climb, and along the way, changing what was thought possible.

Climbing has progressed since their pioneering efforts, with equipment, training and changes to the style, but one thing remains and that is the climbing itself.

The activity has become part of Squamish and grown massively in popularity.

“I’m not at all surprised,” Ed Cooper says. “When Jim and I were there in 1961, we said this place is going to be a great rock climbing centre. We figured that people would come from all over to climb there and that has certainly proved to be true.”

With thousands of climbers coming from around the world, Squamish has become a mecca for this once-fringe activity. The style has changed since those early days when Baldwin and Cooper were hammering pitons into the rock and sweating it out high up the Chief. Today, climbers ascend the Grand Wall in a matter of hours, not weeks.

The difference is akin to felling a large red cedar using a pocket knife verses using a toothy buck saw. In both instances, the undertaking poses a hazard, but with the pocket knife you would have to work at it – just as Baldwin and Cooper did – over the course of weeks.

Felling a massive redwood with a puny knife would also seem utterly impossible at the outset – just as staring up at the yet unclimbed Chief.

In the early days of rock climbing, in Squamish and elsewhere, ropes were made of hemp, rubber climbing shoes didn’t exist and neither did the array of options for protection (Today’s rock climber can choose from dozens of different types and brands of cams, hexes, nuts, tri-cams and big bro’s to protect climbs).

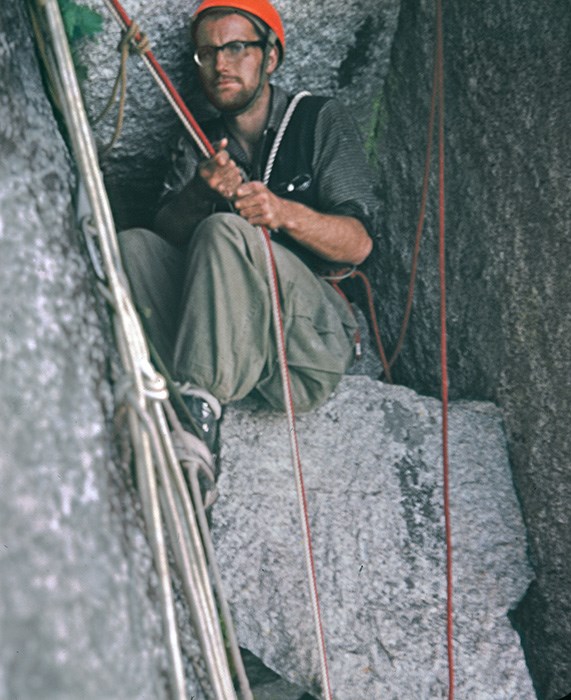

In the 1960s, climbers often used aid climbing to advance their way up the rock. They hammered pitons into fissures and cracks to secure themselves and the rope, and to aid their upward progress.

Today, climbers more regularly opt for free climbing, where the rope and protection are used to arrest a climber in the event of a fall, but not to aid their upward progress.

Climbing was truly a fringe activity in its dawn.

“At that time, there were maybe a dozen climbers who climbed on the periphery routes, the smaller routes, on the Chief,” Cooper says.

As climbing has exploded, the Grand Wall is regularly trafficked. There are often multiple parties climbing on the route at a time and a guidebook reveals the difficulties that are in store.

Belays are bolt protected, and loose rock and lichen has been removed from the rock.

Baldwin and Cooper were explorers as much as they were rock climbers.

“Back then, there were really no guidelines. We did not even have the equipment to handle what was required on the climb,” Cooper says, recalling how the blacksmith in town fashioned some special extra-wide pitons for one portion of the climb – the split pillar pitch.

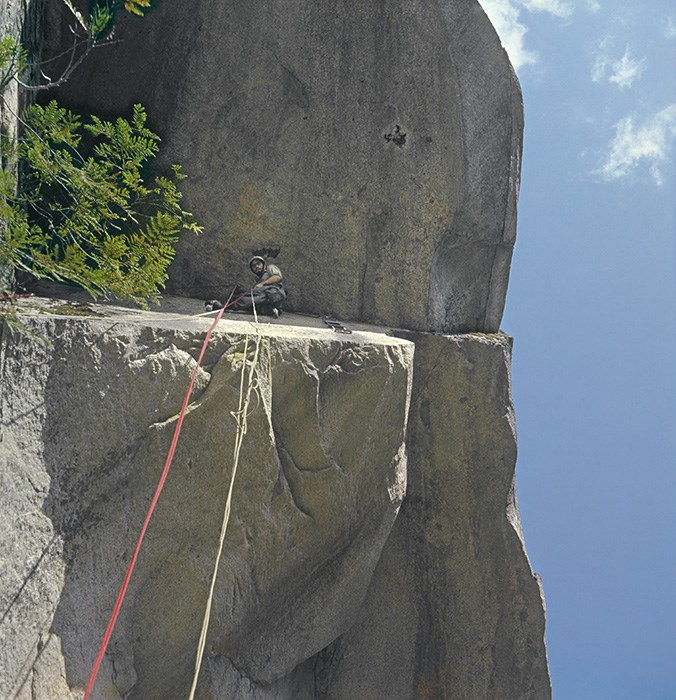

This section of rock climbing ascends a spear of rock that is semi-detached from the main face of the Chief. It begins as a finger-width crack and widens to over a foot, allowing you to see through to the other side of the rock. Upon reaching the top, climbers stood on a little square platform in the sky.

Cooper thinks back to the experience and recalls some of the challenges including rainy weather.

“We just weren’t able to climb all the time and we also came across unexpected problems, which required solutions which we had to make up,” he says.

In the years following his Chief ascent, Cooper went on to establish new routes on El Capitan, Yosemite and the Willis Wall on Mount Rainer. The Willis Wall remains a very serious piece of climbing, even with advances in technology and training.

Cooper thinks of his lifestyle at the time.

“I didn’t have any money – a common problem among climbers even today,” he says with a chuckle.

He didn’t let a lack of funds stop him. Cooper continued to climb and travel through North America, and began shifting his focus to photographing the places he visited as much as just being among the hills.

“In the intervening years, I travelled throughout the U.S. and Canada concentrating especially on the mountains because that was my first ever interest in photography. I take pictures of other things as well now, but mountains are still dear to my heart.”

He wound up living in Sonoma, Calif. with his partner, Debby.

One substantial change to climbing that Cooper notices is the advent of climbing gyms and what they have brought to the activity.

“There wasn’t a single climbing gym that I know of in 1961. None. And now they’re everywhere.”

Cooper was back to Squamish a couple times, most recently to give a presentation about his climbing career at the Squamish Mountain Festival in 2011.

More people come to Squamish to climb each year. However, Cooper’s first ascent, the Grand Wall, remains perhaps the most classic of Squamish lines.

Not only was it the first climb up the iconic Stawamus Chief, but the climbing and the position are spectacular.