Takeo Ujo Nakano would always remember the exact day – the precise hour – his life forever changed.

He was working at the Woodfibre pulp mill on March 16, 1942, almost 100 days after the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor. On that day, all Japanese men aged 18 to 45, who were now referred to as “enemy aliens” by the government, were ordered to move to Vancouver and then sent to road camps somewhere in B.C.’s interior. Nanako was one of them, leaving behind his wife and eight-year-old daughter to face an uncertain future.

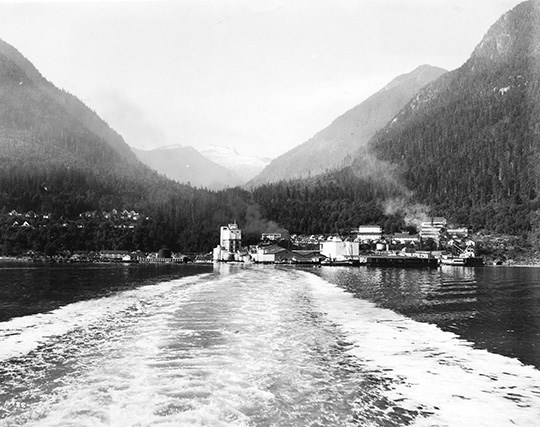

In the early 1940s, young Japanese men made up roughly half the population of 1,000 people living at Woodfibre, a bustling small town seven kilometres from Squamish and accessible only by boat.

Many of the immigrants didn’t speak English, Nakano included, but they still regularly played baseball on Sundays and organized an annual Christmas variety show with the white workers, who were known to live more comfortable lives.

“Woodfibre remains in my memory as an idyllic town where Japanese lived in their tight little community in one section, the whites doing likewise in a better section… I accepted the fact that the whites were the elite. Their men were paid more than we were when they did the same job,” wrote Nakano in the early 1980s in his book Within the Barbed Wire Fence: A Japanese Man’s Account of his Internment in Canada.

It was a Sunday morning in December when the Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service bombed the United States naval base at Pearl Harbor in Hawaii. The base was attacked by 353 aircraft, including fighters, dive-bombers and torpedo bombers, in a preventive action to keep the Americans from interfering with military actions the Japanese planned in Southeast Asia against overseas territories of the United Kingdom, the Netherlands and the United States. In total, 188 U.S. aircraft were destroyed, while 2,403 Americans were killed and 1,178 others were wounded. With that, the United States entered the Second World War.

Taking a much-needed rest before work the next day, Nakano heard of the attack and a piece of his “existence was shattered.”

Climate of fear

This year marks the 75th anniversary of the Japanese Canadian Internment when 22,000 people of Japanese origin – including Canadian citizens – were taken from their homes on the West Coast, without any charges or due process, and exiled to remote areas of B.C. and elsewhere.

“[What happened] represents one of the most tragic sets of events in Canada’s history,” according to the Canadian Encyclopedia.

Many British Columbians lived in a climate of fear after the bombing, supported by several prominent government officials who promoted anti-Japanese rhetoric that stemmed from tension before the war.

Even though most Japanese immigrating to Canada were labourers, “They seemed a threat to the cultural and economic destiny of the white community… “says the afterward in Nakano’s book, written by W. Peter Ward.

In Vancouver, they tended to live in their own small enclaves, including Powell Street in Vancouver and the fishing village of Steveston.

Japanese newspapers, trade unions, business organizations, educational societies and religious associations started. Although their assimilation was limited, their acculturation was more rapid, as they quickly absorbed the language and customs of Canadian society.

But racism was very much alive. People of Japanese origin weren’t allowed to vote or own Crown land, for instance, and attempts were made to segregate Asian children in some schools.

In 1942, the B.C. government ordered all Japanese men under 46 years old – around half of Woodfibre’s population – to leave their work and families for road camps scattered mainly throughout the Interior of B.C. At first, women and children, as well as men born in Canada, were allowed to stay behind. Later on, many of these people were ordered to evacuate as well.

“I remember the compulsory nightly blackout, meant to thwart the activity of Japanese bombers that might fly over British Columbia,” Nakano writes in his book, which has been translated into English and is available for loan at the Squamish Public Library.

During the war, Squamish may have been relatively isolated but the threat was still felt close to home.

Squamish was a strategic harbour due to its railway and marine facilities, and considered a bombing raid target, notes local historian Eric Andersen. A strict “lights-out” policy was enforced until after the war ended, but no bombing raids took place. However, between November 1944 and April 1945, around 9,000 balloons carrying incendiary bombs were sent from Japan to set forest fires on their enemies’ territory. Andersen says around 300 landed in North America, including two that have been found near the Sea to Sky Corridor – in Tisdale south of Pemberton and on Gambier Island.

“The Canadian military told the RCMP to interrogate Japanese Canadians about the balloons, but the RCMP replied that any assumptions that the Japanese maintain an espionage network in Canada ‘has no foundation and cannot be entertained in light of our situation,’” Andersen tells The Chief. “Many people saw the reality. They had a realistic perspective. There was a substantial second-generation [of Japanese people] living at Woodfibre, who were fluent English speakers and played basketball against Squamish.”

Wartime tension was also evident closer to Squamish.

In Smoke Bluff Park, near the Neat & Cool climbing area, caves that were used as a training and hideout place for Pacific Coast Rangers, a militia unit, have been discovered.

“They were preparing for invasion,” said Anderson, adding that there are plans to put a plaque up at the historical location.

This fear led all people of Japanese ancestry to be excluded from a 100-mile zone inland from the Pacific Ocean – including Woodfibre.

“As the day of departure drew nearer, tensions mounted in the Japanese community,” writes Nakano.

“In the late afternoon the Woodfibre dockside was crowded with our wives and children seeing us off. It was one great confusion. Concern about the uncertain future compounded the anxiety of parting.”

Besides the uncertainly of leaving their lives behind, they were afraid of the possibility of starving in the cold weather and dying in natural disasters, such as avalanches. “Facing the docks, I smiled bravely and waved…. My wife had some last-minute words for me, but her voice was drowned out in the tumult.”

The British Columbia Security Commission, the federal agency created to carry out the evacuation, moved the men methodically.

A reporter for the English-language Japanese newspaper The New Canadian wrote in May, 1942:

“The Howe Sound area, including the pulp and paper mill of Woodfibre and the mining venture at Britannia, was cleared today of all persons of Japanese origin.

The Union Steamship S.S. Lady Cynthia was due to arrive in Vancouver about 7 p.m. with 250 evacuees, completing the evacuation of the entire coast, except from Vancouver and district and the Fraser Valley.”

‘Herded’ away

There was a sense of tension and nervousness as the men got off a ferry in Vancouver and were loaded onto waiting trucks that were driven to an assembly centre at Hastings Park Exhibition Grounds – the location of the today’s annual Pacific National Exhibition (PNE) – and “herded” to a building that was normally used to house livestock. Straw-filled mattresses were laid row-upon-row on the bare concrete floor.

Canadian National Railway train brought the men to a string of road camps in the Rockies and along the Alberta border.

“We Woodfibre men were in a group of 150 destined for Yellowhead, nearly 500 miles from Vancouver,” Nakano says.

The camp, near Jasper, Alberta, was deep in snow and had 12 freight cars on loan from CNR to house the men.

Each car had six bunk beds, a coal stove the men were served a lot of “good food by white cooks.”

Each day, as the men did “make-work” projects, Nakano longed for his family. His life was now a far cry from what he planned for when he moved to Canada in his mid-teens during the early 1920s.

He grew up on a rice farm, which, while far from rich, meant his family had greater status as landowners.

He graduated from agriculture high school and learned about poetry from his father, who was well known locally for his haikus.

Growing up on a rice farm, he had the work ethic to help at his uncle’s berry farm near Maple Ridge, with the dream of owning a large farm of his own one day. He went on to work at Woodfibre when the economic decline cut his employment short after two years.

Forever changed

As the war progressed, Nakano was moved to another road camp and told he would be reunited with his family in Greenwood, B.C., but was then ordered to go to a subsequent camp in the Interior. He was bitter and protested the decision, so the Security Commission freighted him off to a camp in Angler, Ontario.

Finally, in November, 1943 – 22 months after he was forced to leave Woodfibre – Nakano was granted permission to reunite with family.

After the war, he settled with his family in Toronto, continuing his cultivation of tanka, a form of poetry that had distracted him from his grief while at the camp.

Like Nakano, many Japanese families never returned to B.C.

Public opinion and political pressure strongly opposed the evacuees’ return to the former homes, the book says.

The majority moved to the prairies or eastern Canada, leaving only 30 per cent of the original 20,000 in British Columbia.

At Woodfibre, people from China – which was allied with the U.S. and Canada in the war – eventually replaced the Japanese workers, says Anderson. (In fact, many people of Chinese origin recently attended a reunion for former Woodfibre townsite residents.)

In 1950, a report by the federal government found that the amount paid to Japanese Canadians for their property – including houses, businesses, vehicles and other belongings – was substantially below fair market value, according to the Canadian Encyclopedia. In the end, many were unable to recover much of their losses. Racism persisted after the war in more subtle forms and government policies were relaxed. “One reason for this change was that, once dispersed, the Japanese no longer seemed the social and economic peril they had once appeared.

Obviously, as well, Japan’s defeat had eliminated all prospect of a military threat, either external or internal,” the book continues.

In 1949, the last government restrictions on Japanese-Canadians were removed but Japanese-Canadian society had been altered permanently. However, by the late 1940s, most Japanese Canadians had been born and raised in Canada and were no longer separated by a wide cultural gulf.

“In the process of becoming Canadian, the Japanese had finally won a measure of acceptance,” Nakano concludes.

In 2012, the B.C. government apologized for its part in the internment.