As Sean Roberts is standing outside of The Squamish Chief's offices, a few boys — who are about 12 years old — walk up to him.

"What is that?" one of the boys asks, gesturing toward his prosthetic right arm, clearly impressed.

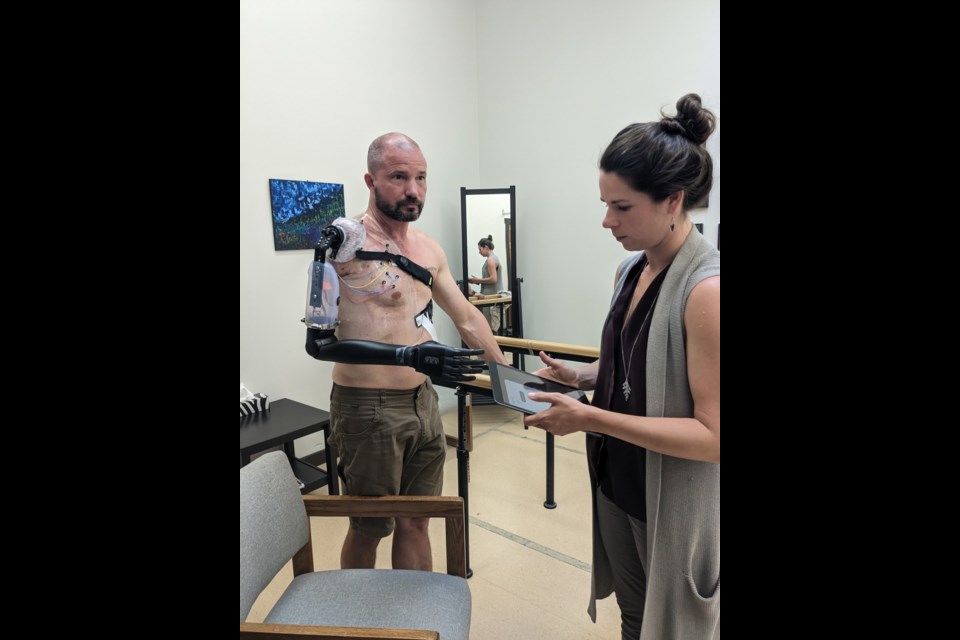

Roberts explains that it is a robotic arm, which uses AI technology.

He flexes his hand, and the futuristic-looking black fingers open and close.

"Cool! That is sick, man," one of the boys said.

For Roberts, being GenX — he's 50 — the slang term would have been "excellent" when he was the boys' age.

"What happened to your arm?" the boy asks.

Roberts explains that he had a disease and had to have it removed. Now he has this, he says, looking back at his prosthetic.

The conversation is matter-of-fact, on both sides.

"Cool," the boy says again.

Roberts smiles as the boys walk off.

The local had his arm amputated in July of 2021, a "major milestone" in his lifelong fight with complex arterio-venous malformation (C-AVM) and genetic mosaicism.

The Squamish Chief sat down with Roberts for a long chat that ranged from discussing his arm, what he has learned about disability, what needs to change on a personal and national level, how great some folks are in Squamish, and how readers can help.

What follows is a version of that conversation that has been edited for length and clarity.

How did you end up in Squamish?

I moved here seven years ago. I was living in Ottawa because I had been working as an economist for the federal government before I went into medical retirement. But I don't deal well with climactic shifts. Too hot, too cold, I get very sick. And so, Squamish was the natural place for me because it had accessibility to Vancouver for specialized treatment, and you know, is right between there and Whistler. Who wouldn't want to live here, right? Luckily, I got in before this place exploded.

But, by the time I got here, unfortunately, the disease continued to worsen to the point where I was just bedridden. The first five years here, I was basically bedridden, which is a nice way to put it that people want to hear.

Do you mean you have to kind of dress up the situation for other people?

Bedridden is a polite term for what it really means — not being able to get out of bed to go to the washroom. Not being able to feed yourself, being socially isolated. You have got to dress it up for people, though, because what I've realized is that in order to have any sort of social interaction, you have to basically be your own PR firm 24/7, which is exhausting. But if you want a social life, unfortunately, that is the way it has to be.

I've gone through phases. In the beginning, this disease was very grotesque, and children would cry when they saw my arm. It was that bad.

People don't see you; they see this thing. And so four or five times a day, at least, you get people who would ask personal questions about my arm. Surprisingly, it was people in healthcare, strangers, who would feel entitled to come up and ask me. Eventually, I said, No, that's not cool.

I did start correcting people. I said, “My name is Sean.” I am a human being. If you want to address me, address me as “Hi, my name is” [and] introduce yourself. Don't go right into somebody having a disability as your entry into a conversation, right? That's rude.

What was really interesting to me was the incredible demarcation between pre-and post-surgery. "What's with your arm" became "How can I help you?” Instantly. People's attitudes, behaviours, and how they approach me changed 180 degrees.

You have talked about hitting rock bottom. Can you say more about that?

About six months before the amputation, the only option that I was able to see in my future was doctor-assisted suicide through Canada’s MAID program. But then after a couple of weeks, I said this is stupid. I have to give it everything I have and do one last major push.

A friend helped me get started in the gym. I ended up going every day, sometimes two times a day, at Mountain Fitness.

I had local dietitian Susie Cromwell help me with my diet. I lost 50 pounds. And then the surgery happened. That was two years ago.

What is more advice for approaching you or anyone who looks different or has a disability?

View everybody as a human being first. Looking at it through that lens of our own individual frailty and seeing the whole person, not just the obviousness of what their immediate challenge is. I think that, just in general, is the best way to approach things.

Kids are great: "How come you lost your arm?" Yeah, good question.

If you see someone struggling, maybe say, "Hi, that looks challenging. Are you good?"

We tend to forget. We get so myopic on just whatever's in front of us that day that we forget our humanity and the humanity around us.

The more anxious and more frantic the world gets, the less human we become. But that's when we need to be the most human. That is when we may need to be the most compassionate, understanding and supportive of each other.

You talk about the difference between available help and accessible help for folks who are disabled. Can you explain that more?

The tools and adaptation strategies for this are insanely expensive. A cutting board for a one-handed person is $250. There are things that are available, they are not necessarily accessible to people who need them.

The problem, as I've learned, is that there are two tiers when it comes to assistance. The first of which is insurance. You have a motor vehicle or a workplace accident that leads to injury, you have somebody to sue, right? There's somebody who is going to be responsible for what happened to you. If you were born with it, or something happened at home, or what have you, you're in a second tier of insurance, where you get the bare minimum, if you're lucky.

All this stuff is out of pocket to the tune of about almost $30,000 for me so far. I have had to cut things out. Like, I don't go to the gym anymore. I just can't afford it. That was one of the things that had to go after the amputation, and it was brutal — it's still brutal. I have to get shirts altered for my prosthetic arm. I still haven't had my car switched over for one-handed usage. Another example is replacement shoelaces, a toothbrush that doesn't roll over when you put toothpaste on it. Soap dispensers that you can grab with one hand, a sticky with a sponge for on the wall of your shower, so you can wash your arm and back. It's perpetual.

A prosthetic for mountain biking is definitely something that is on my list, but it is like $20,000. One of the things I'd like to start getting back to is one of my hobbies, woodworking. But you need another prosthetic for that.

So there's all these cool things, but they're very inaccessible?

For someone like myself who does not accept help well, it puts me in this position where I am completely dependent on others. And that, for me, that's the most brutal part because of what it does to self-esteem, dignity.

But I have to say that this community has been amazing. Awesome.

How so?

My approximately $150,000 prosthetic was paid for by PharmaCare and Sunlife and the rest was chipped in by The War Amps.

But it goes back to local Tania Chabot, who is my prosthetist. She lives here but works out of Russell Prosthetics in the Lower Mainland. She took this on: got all the funding and everything else lined up. She was 1,000% committed to getting me this arm.

And here's another example, Betty Han, who owns Cloud 9. She saw me and my dog Skye walking around the salon, ran out to ask how I cut my nails and offered to help me. People like Betty make this community what it is. That stuff is important.

So what do you need from folks now?

I think primarily is just a bit more awareness and attention to the fact that you never know who you're talking to. There are so many hidden disabilities as well. There are so many challenges that people face. Mine is obvious. You've got to be compassionate. You've got to keep that stuff in mind. You never know how a misplaced comment is going to affect someone for the next three days. Just be compassionate. Beyond that, on a personal note, I’m looking for a family doctor like so many people here. And I still have so many things I need to save up for. I need help.

Find out more about Roberts or donate to him by going to his website: lifeampd.com.

**Please note that this story has been corrected since it was first posted to say that The War Amps paid for the remainder of the arm, after PharaCare and Sunlife paid their portions. This division was not clear in the original>

About a local is a regular column about interesting Squamish residents. To be considered, email [email protected].

.png;w=120;h=80;mode=crop)