Several years ago, I attended a slide show presented by a prolific Coast Mountains explorer, John Baldwin, at the Squamish Public Library. A single image captured my attention more than any other. It was an alpine lake, framed by dramatic mountain peaks just beyond its edge. Baldwin revealed that the photo was taken on the pass connecting Princess Louisa inlet to the Elaho Valley, one of his favourite routes in the Coast Mountains. Practically in my backyard, yet far enough away to offer the tantalizing trifecta of challenge, discovery and mountain solitude. I knew I had to go there.

This July, I had the opportunity to make the trip, along with three friends: Bridget, Mark and Keara. The route covers 25 kilometres of some of B.C.’s most spectacular mountain terrain, beginning at the stunningly beautiful and historic Princess Louisa Inlet, summiting Mount John Clarke, and exiting at Sims Creek just before it merges with the upper Elaho River. (The route can be done in either direction; many people go from east to west.) To save us hours of logistical choreography with ferries and car drops on the Sunshine Coast, we treated ourselves to a flight from Whistler to the coast.

At the head of Princess Louisa Inlet, the picturesque Chatterbox Falls greets boaters visiting the provincial park. The trail heading up to our first destination, Loquilts Lake, was well marked and has been in existence at least since the 1880s, first as a logging road and later as a trapline. It rises a steep 1,350 metres from sea level in the manner of most coastal trails: straight up. For reference, if you stacked the Stawamus Chief trail on top of the Grouse Grind and added a couple of rocky sections with ropes to assist, you would have something similar. We dubbed the technical term for this style, “NFS” – No F-ing Switchbacks.”

After six hours of heavy sweating we reached Loquilts Lake, and my fabled tarn. It was every bit as gratifying as we had hoped – the mountain view beyond made all the more glorious by the work we put in to earn it. The lake, being smaller and warmer than the larger Loquilts Lake, rewarded us with a refreshing swim. Once the clothes came off, as alpine custom goes, they stayed off for the rest of the day. An exploratory wander brought back an unexpected discovery: four folding chairs and a folding table! They were found folded up in their bags, nearly new, and neatly placed on a rock. Only a helicopter could have brought them there, as no one would lift those heavy luxuries up that trail and the lake is too small for a plane to land. Whoever left them, and whether it was by accident or to return for frequent heli-picnics, we will never know.

Sun bathing in the warm August sun, with a slight breeze to drive the mosquitos away, and a “furnished” campsite with million dollar views, we wondered if anything could make this moment more perfect. “Only if dinner were served by a naked man,” quipped Keara. Just then Mark appeared wearing a bowtie and a button-up shirt (only). “Ladies,” he said, “Dinner is served.” A flask of whiskey was passed around as an aperitif, and pesto pasta was savoured in the twilight of an alpine sunset. Perfection had been achieved.

The only thing that tainted our mountain paradise was knowing that it would soon end, and the dreaded Bug Lake trail awaited us. Bridget had hiked up the Bug Lake trail from the Elaho side seven years earlier and the descriptor that came most vividly to her memory was “heinous.” “What is that old saying from Casablanca – ‘We’ll always have Paris’?” she said, trying to relieve our trepidation. “We’ll always have Loquilts!”

But first, a mountain to climb. We packed up camp and continued our ascent, passing the still snowy Contact Lakes. From here we ascended rock and heather newly freed from snow to gain a moraine that provided straightforward travel toward a lower peak directly in front of us. Where the moraine was swallowed by snow, we donned crampons and crossed over the glacier to a rocky island, and from this point ascended 600 metres (1969 feet) to gain the snowy ridge crest, travelling along the crest for about 100 metres before removing our crampons for the final 15 minutes of rocky scrambling to reach the summit of Mount John Clarke.

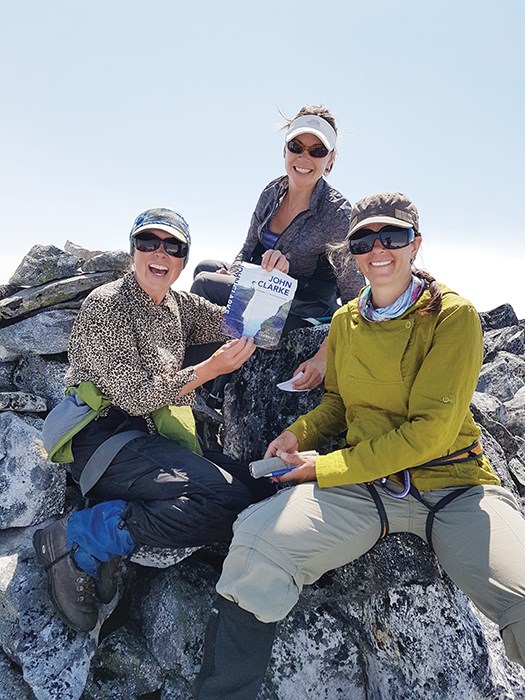

Clarke was a prolific mountaineer, explorer, conservationist and educator in the Coast Mountains for 40 years, often disappearing for months at a time on solo traverses, logging hundreds of first ascents in the ranges between the Lower Mainland and Prince Rupert. Passionate about sharing the joys of mountain travel with others, Clarke teamed up with Lisa Baile to co-found the Wilderness Education Program, designed to help young people connect with nature. Tragically, he died of a brain tumour at the age of 57. Baile wrote his biography, and the jacket of her book was tucked into the register at the summit cairn. I signed the register in memory of a friend who also died tragically before his time. The mountains remind us, more than anything, of the grand and perilous adventure that life is, every day a gift.

Leaving the summit, we were still several kilometres from Bug Lake and it was getting late in the day. Could we find a decent camp spot on the uninviting rocky ridge that lay ahead of us, or should we camp on the glacier, where at least we knew there was safe, relatively flat terrain to camp on? Previous trip reports had mentioned a large flat rock that made an excellent camp site somewhere on the ridge at 1,933 metres (5,800 feet), described as “the Jesus Christ stone, a large flat rock suitable for worship and feeding the multitude.”

We decided to press on in search of this holy grail before dark. Within a couple hours we emerged upon an appealing site of several wide, flat rocks welcoming us to drop our packs and rest our feet. After 12 hours of hiking, dinner never tasted so delicious. The multitudes of mosquitoes sharing our sanctuary were no less satisfied, delightedly gorging themselves on the meal brought from heaven.

The next day we made our way over the wide spine of the ridge and down to Bug Lake, where the “descent into madness” began. The 800-metre drop was some of the steepest and gnarliest terrain I have encountered and not one of us escaped unscathed. Once we reached the bottom, only 15 kilometres of abandoned logging road and a burly creek crossing remained between us and the ciders we had stashed in the car for our return. Crossing in a diamond formation, each one holding onto and supporting the other for stability, we navigated the rushing waters safely and reached our reward.

Toasting our success, we reflected on our journey. We had effectively walked from the Sunshine Coast back to the Squamish river system. Through our shared challenges, joys, sacred moments and playful irreverence, we built memories we would treasure for years to come. And, as Bridget so aptly put it, “We would always have Loquilts…”