The pleas of bereaved Squamish parents have reached the ears of the leadership of the provincial government.

After Brenda Doherty went public about her 15-year-old daughter Steffanie Lawrence’s fentanyl overdose death in January — and the herculean efforts she and her family went through in an effort to get the child help — Minister of Mental Health and Addictions Judy Darcy sat down with the girl’s parents.

“During that conversation, the minister heard about Steffanie’s journey through the mental health and addictions system, and also learned about the significant challenges experienced by the family and their views on how the system let them down,” a ministry spokesperson told The Chief in an email.

“Steffanie’s experience, and the experience of her family, underscores the challenges many families across the province have when trying to navigate a system that can be fragmented and uncoordinated,” the spokesperson said.

“The ministry is working to address those gaps and “build a seamless and co-ordinated system.”

Darcy asked Steffanie’s parents to be involved in helping change the province’s mental health and addictions system.

Her parents have been calling for a secure care act that would allow desperate parents to have their child forcibly put into treatment.

According to Mayor Patricia Heintzman, approximately eight people in the Sea to Sky Corridor died in 2017 from an opioid overdose.

Proposed bill

North Vancouver–Seymour MLA Jane Thornthwaite has re-introduced private member’s bill M 240 — 2017: Safe Care Act, 2017.

Thornthwaite, Liberal mental health and addictions critic, reintroduced the act in late February.

It would be a court-mandated last resort for those who are desperate to help their children, Thornthwaite said.

It would allow parents to have their children — aged 12 to 19 — committed for a short time against their will.

Former MLA Gordon Hogg originally introduced the bill in spring of 2017 prior to the provincial election.

Had the Liberals formed government, the bill would have been brought forward as a government bill, Thornthwaite said, acknowledging parents of vulnerable youth have been pressing for there to be such a law.

Bills must pass through three readings and study by the Committee of the Whole House before becoming law.

Only 1.8 per cent of votes by BC MLAs from 2013-16 were cast out of party lines, according to data collected by Imagine X, but Thornthwaite said, “Where there is a will there’s a way.”

Steffanie’s father, Shaun Lawrence, started a Change.org petition directed at Darcy asking her to support the bill. The petition has garnered close to 9,000 signatures as of this week.

Other experts, including those from the Ending Violence Association of BC and the Representative for Children and Youth, did not support the proposed act when it was first introduced, arguing that until a “culturally competent network of diverse and voluntary services are available to children and youth across the province,” incarcerating youth for treatment should be avoided.

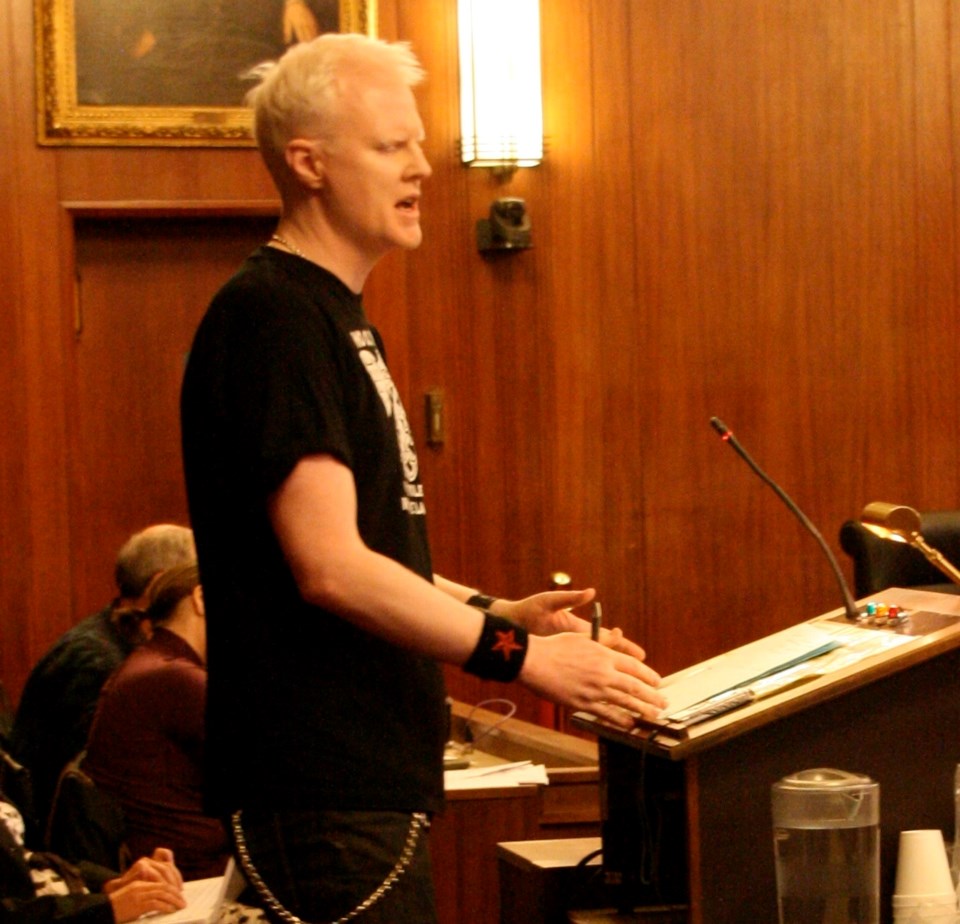

Recovering addict and long-time activist for harm reduction Garth Mullins, said, though he is not a parent, he has concerns about secure care proposals.

“The force of the state has not been very effective at addressing this problem,” he said.

Instead, parents need to have access to the resources so kids can get help early: “We have got to make it so the second a parent or a kid feels like something is amiss, there are services that can jump in immediately. Not this insane scramble for months to try and find what is often a really dodgy and ineffective treatment.”

If we are going to go to this massive extreme of incarcerating kids for their own safety, we ought to start with the things we already know that work including treatment and harm reduction.”

Mullins said there are a lot of stereotypes about who is at risk of an overdose.

Coroner statistics show most people who die from overdose die alone at home.

“The idea of a super-marginalized drug user in an alley in the Downtown Eastside [of Vancouver] is not really representative,” he said. “The idea of the drug user that people should be thinking of is their neighbour, their co-worker, their friend and the stigma makes it invisible — it forces people to hide... People ought to know if it is not in their workplace or school or their bloodstream, it is coming."

Mullins advises parents take Naloxone training with their teens.

Naloxone is the antidote to opioid overdose.

“Everyone gets a good first-aid skill they can use anywhere and the training would provoke the kind of discussions that would probably help parents know what is going on,” he said.

Squamish author Graham Fuller’s son Luke died of an overdose two decades ago.

“Youth at any time, at any stage in history goes through the crisis of becoming mature and probably in contemporary life in many ways, technology has increased those pressures,” he said, reflecting on the current opioid crisis.

Social media has raised the bar so high in terms of what kids have to do to fit in, Fuller added.

Regarding secure care, he said some degree of community intervention might be helpful.

“If it is enlightened in its approach,” he added. “But there’s no magic bullet either.”

From his own family’s experience, Fuller believes support groups can be very helpful.

While living in California during the height of his son’s addiction, Fuller, his wife and son were required by a court to go to community-sponsored meetings twice a week.

“I think that had a lot of benefit,” Fuller recalled.

Hearing other families’ struggles was really educational and comforting, he added.

Fuller said it is important that parents realize the limits of their powers to completely control the situation.

For families in the midst of a child’s addiction, it is also important they take care of themselves so they can be there for the child, he said.

“If you can’t take care of yourself and your own mental health and relationships, then you are ill-equipped to help a child,” he said.